An occult doomsday cult in 1690s Philly

In the 1690s, a Transylvanian-born mystic, occultist, musician, and writer named Johannes Kelpius led a group of forty Rosicrucian monks to colonial Philadelphia await the end of the world.

Though Kelpius and his group of highly-educated mystics were disappointed when the day of revelation didn’t come, they made the best of their new home, building an observatory, a botanical garden, and an orchard. They also wrote poetry, composed music, and studied alchemy, divination, and conjuring.

Records show that they experienced a number of paranormal events, including the sighting or a ghostly figure at the edge of the woods during a celebration around a bonfire, blue flames emerging from a fresh grave, and more. There are also stories of Kelpius’ followers performing astral projection, and Kelpius himself possessed a magical stone that he guarded fiercely, but which has since vanished.

The story of Kelpius is one of the weirdest and most elliptical stories I've researched; when I did a podcast episode about it two years ago, I included every scrap of information that I could find about him. Which wasn't much.

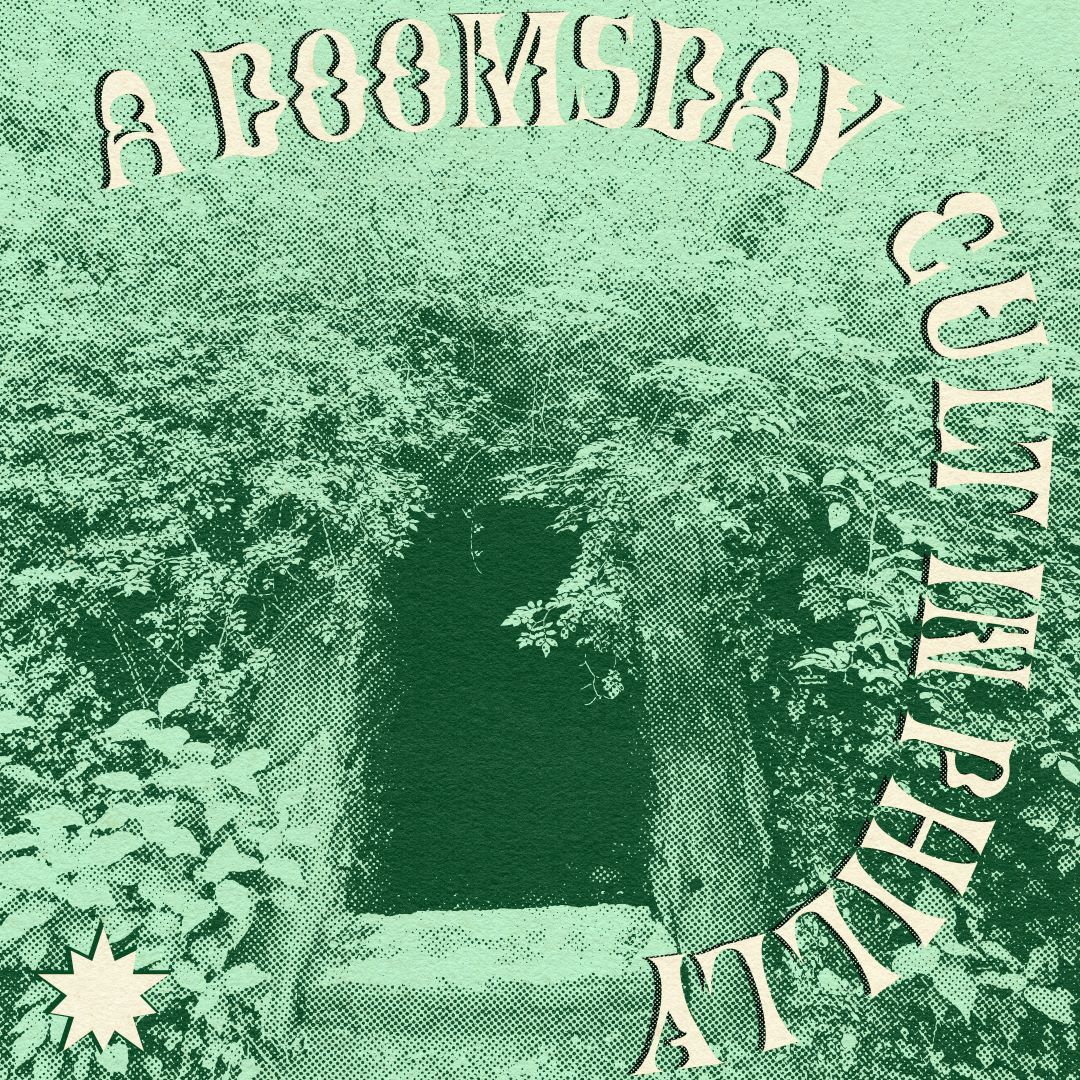

But I haven't been able to stop thinking about his story since; a few months after releasing the episode, I even went to Philadelphia and dragged both my wife and our friend to the "Cave of Kelpius," which is tucked in the woods of a particularly lush and beautiful city park. Maybe it's just because it was a sweltering, suffocatingly humid day, but we all got a bit of a strange vibe from the cave and didn't want to stay long. It was a heavy-feeling place.

Because the episode is so old, I wanted to give it a little essay-style refresh. So here's an the story of 1690s doomsday cult.

“Deep in the woods, where the small river slid

Snake-like in shade, the Helmstadt Mystic hid,

Weird as a wizard, over arts forbid . . .

Whereby he read what man ne’er read before,

And saw the visions man shall see no more,

Till the great angel, striding sea and shore,

Shall bid all flesh await, on land or ships,

The warning trump of the Apocalypse,

Shattering the heavens before the dread eclipse.”

– John Greenleaf Whittier, “Pennsylvania Pilgrim” 1872

Johannes Kelpius

Johannes Kelpius was born in Transylvania–yes, really, Transylvania–in 1667. His birth name was Johann Kelp. But back then, it was customary for academics to receive Latinized names, so after attending a university in Bavaria, he received his new name, Johannes Kelpius.

While at the university, he became interested in Pietism, a Lutheran movement that emphasized biblical doctrine, as well as piety on an individual level. I don't remember learning about Pietism in school, but apparently it was a big influence on Protestantism in North America and Europe. It focused on frugality, restraint, and order, but there was also a hint of mysticism tied into it. Esoteric and heretical Christian ideas were often lumped into Pietism.

When he was twenty, Kelpius became a follower of Johann Jacob Zimmerman, a German nonconformist theologian, mathematician, astronomer, and former cleric whose belief in the upcoming end of the world—and criticism of the state church—cost him his religious position. Zimmerman’s followers were all highly educated, and Zimmerman called them “the Society of Perfection” or “Chapter of Perfection.”

Though nowadays we tend to view the occult and religion as separate, people used to view them as connected. So Zimmerman’s group was full of highly educated religious people who have been referred to as cabbalists, hermeticists, Rosicrucians, and general students of the occult. From his published works, it’s clear that Kelpius was familiar with Rosicrucianism, and it's likely that Zimmerman and Kelpius met at a Rosicrucian or cabbalistic meeting.[^1]

At any rate, Zimmerman determined that Revelation—you know, the end of the world—was at hand, and that the place to be for that was Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

Waiting for the end of the world in Philly

In 1682, a Quaker named William Penn founded the city of Philadelphia, which was, of course, located in Pennsylvania Colony. The colony had a reputation for being very tolerant when it came to European religions.

If you open your Bible to Revelation 3:7-13, there’s a section about the church in Philadelphia. Verse 11 has a nice little tidbit: "I am coming soon" (from the KJV). (Of course, the Bible refers to present-day Alaşehir, Turkey, which was once called Philadelphia.)

But, between the apocalyptic Philly-related Bible verse and an openness to esoteric religions, Philadelphia was the perfect place to import a doomsday cult.

Arriving in Philly

As the group that followed Zimmerman prepared to leave for the American colonies, Zimmerman died suddenly, leaving twenty-seven-year-old Johannes Kelpius as the leader of the group.

Around 1694 (maybe a bit before?), the group of about forty people arrived in Maryland. They went on to Philadelphia, which at the time was what we’d consider very small, with only about 500 houses in the whole city. The settlement was also on the edge of the wilderness.

The number of monks who came to Philly–forty–is significant. During the Biblical flood, it rained for forty days and forty nights. Moses spent forty days and night at Mount Sinai. Moses and his crew wandered the desert for forty years. Jesus fasted in the desert for forty days and forty nights. You get the idea. The number comes up a lot in the Bible.

In Philly, they built a large meeting house, which was—you guessed it—forty square feet. The meeting house was said to have a telescope, and it was the first observatory set up by colonizers in the "New World."

The group of monks went by several names, including “the Hermits of the Wissahickon,” “The Society of the Woman in the Wilderness,” “the Hermits of the Ridge,” or the “Mystic Brotherhood.” The Woman in the Wilderness was a character from the Book of Revelation, and I just love the image that the name evokes—it strikes me as scary, mystical, and poetic.

Waiting for the end

They settled in and waited for the end of the world, which was supposed to be in 1694.

As you might have already figured out, the world did not end.

The Wikipedia page puts it very poetically:

Though no sign or revelation accompanied the year 1694, the faithful, known as the Hermits or Mystics of the Wissahickon, continued to live in celibacy, searching the stars and hoping for the end.

So they kept waiting.

In the meantime, they build a school for kids in the neighborhood, held worship services that were open to the public, and—since they were well educated—shared their medical knowledge. They also opened a botanical garden and orchard, studied astronomy, wrote poetry and music, and dabbled in alchemy, divination, and conjuring.

Things seemed to be going pretty okay, aside from the world not ending.

The end of Kelpius

Kelpius apparently had a dramatic fantasy for his own death: He believed that he’d be transfigured like the prophet Elijah and brought into heaven in the flesh.

As his health declined, Kelpius spent three days praying for that grand end. Eventually, it became clear that wasn’t going to happen. So he moved onto more practical preparations, speaking to his friend Daniel Geissler and asking him to throw a mysterious sealed box into the Schuylkill River.

Geissler knew that Kelpius had been searching for immortality (remember, Kepius dabbled in alchemy), so he thought that the box might contain something to help with that (like a philosopher's stone). So instead of throwing it into the river, he hid it on the riverbank.

According to legend, when Geissler returned, Kelpius looked at him and said, "Daniel, thou hast not done as I bid thee, nor hast thou cast the casket into the river, but hast hidden it near the shore."

Now convinced that Kelpius had mystical powers and was not to be lied to, Geissler went back and threw the box into the water. He claims that when he did it, the box exploded, followed by thunder and lightning.

We have no idea if this story is true, of course. To me, it has the sheen of myth-making. But it's charming.

A Philly Voice article points out similarities to the King Arthur myth. Kelpius' request sounds like when Arthur tells a knight to throw Excalibur, his magical sword, into the enchanted late. Though the knight doesn’t want to at first, he eventually tosses it in, and the lady of the lake emerges to take it. Folks have pointed out that since Kelpius and his followers were highly educated, they would have been familiar with the legends of King Arthur.

Kelpius died of tuberculosis, or maybe pneumonia, in 1708, at the age of thirty-five. His death was supposedly caused by exposure during the cold winter; as an ascetic mystic, he probably didn’t always make healthy decisions.

He didn't get an Elijah moment of transfiguration, but when they lowered his coffin into his grave, they released a white dove. A nice touch, I think.

We don’t know where Kelpius was buried. But we do know that after his death, his community declined.

Paranormal happenings

Starting prior to Kelpius' death, every year, the monks celebrated the anniversary of their arrival on June 23, which is St. John’s Eve. St. John’s Eve is the day before the feast of John the Baptist. Because it nearly coincides with the summer solstice, it can be a pretty big celebration in some places. Traditionally, people light bonfires and collect medicinal herbs.

To celebrate, the monks would light a bonfire in the woods and then scatter the embers. This was meant to symbolize how the sunlight wanes between summer and winter solstice.

In 1701, after the St. John’s Eve bonfire, the monks are reported to have seen "a white, obscure moving body in the air, which, as it approached, assumed the form and mien of an angel…it receded into the shadows of the forest and appeared again immediately before them as the fairest of the lovely."

That wasn't the only paranormal occurrence. After Kelpius' death, it’s said that six monks still followed the lifestyle after the others left. People in the area would occasionally see them walking single file, wearing hoods and sandals.

It’s also said that six ghostly figures are still seen on nearby Forbidden Drive.

The Cave of Kelpius

Today, one of the caves where this cult lived, called the Cave of Kelpius, stands in Philly, on a hillside in Philly’s Fairmount Park, above the Wissahickon Creek near a Hermit Lane.

The cave isn’t technically a cave: it’s been described as “a manmade structure about the size of a springhouse.”

Springhouses were typically constructed on top of a spring to keep detritus from falling in and contaminating the water source. Some people don't think that this was Kelpius’ cave at all, and that it was just a basic springhouse.

Whether or not Kelpius ever used the structure, it still memorializes him. Today, a marker placed by the Rosicrucians declares that this was the site where Philly’s first mystical guru came to meditate and wait for the second coming.

This article doesn't link to sources as comprehensively as usual, because I wrote it based on my original episode notes, which I penned when I was worse at adding specific in-line citations. But all of the sources I used are linked at the bottom of the episode shownotes page.

[^1] In an article called German Cabbalists in Early Pennsylvania, Elizabeth W. Fisher writes about Kelpius and his comrades, and it has a good summary of what Rosicrucianism meant at the time.